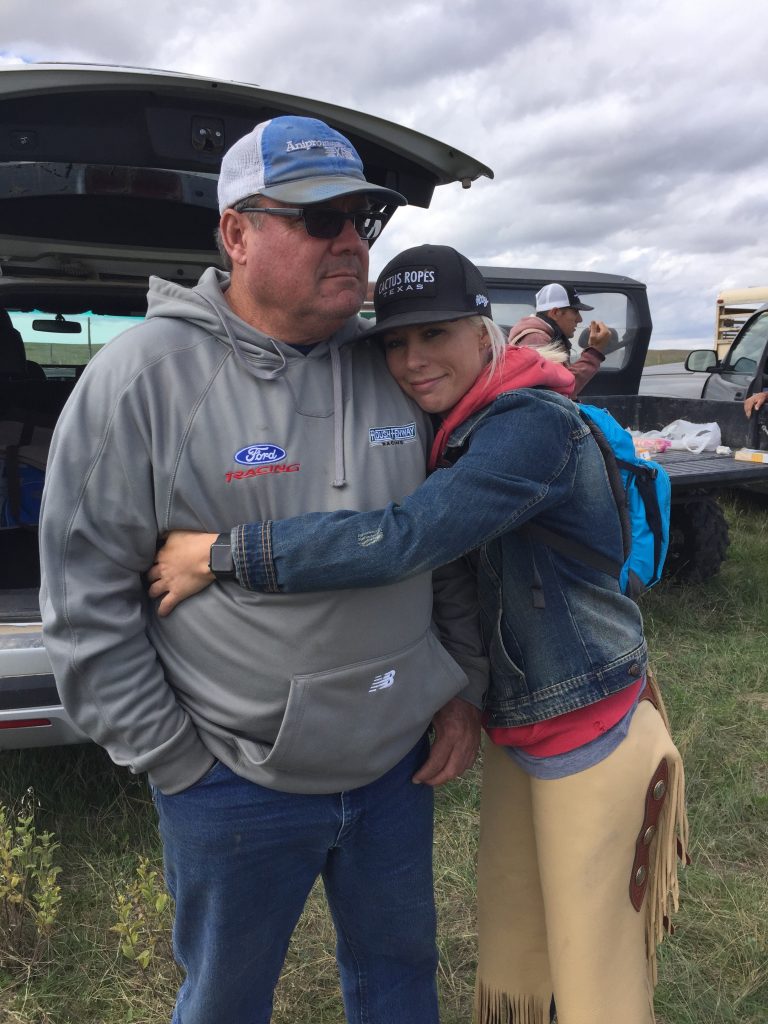

Harris Family

to highlight the families who make up our state’s No. 1 industry and help feed the world. This month we highlight the Harris family, pictured here: Kasi & Klay

and son, Rhyder; Kim; Kalen & Heather and children: Dean, Kade, Koby, Jace and Harley; Kelsie (Harris) & Luke Meeks and their children: Narley and Radley.

By Lura Roti for South Dakota Farmers Union

In their 30s, the Harris kids are still old enough to remember the days before air-conditioned tractor cabs. In fact, when they talk about how growing up on their family’s Bennett County ranch taught them responsibility and work ethic, Kalen, 36, Klay, 33, and Kelsie, 31, give quite a bit of credit to an old 300 International tractor.

“When we’d rake hay, it wouldn’t go up the hill, so you had to go all the way around and go back and forth,” Kalen recalls.

“And when you were done, you had to park it on a hill so it would start,” Klay adds.

“I remember I had to let it roll down the hill to start it. And my brothers only let me rake because they were so picky about everything,” Kelsie says.

Klay and Kalen were 6 and 8 when they started haying. Kelsie says she was closer to 13. They all learned how to drive on that old 300 International.

Summing up the value of growing up on a western South Dakota farm/ranch, their mom, Kim, says, “You learn to work hard and deal with what you get.”

Growing up raising crops and cattle together, with their parents, Kyle and Kim, ranching full time became the career of choice among the Harris kids.

“We have worked side-by-side since he was 8 and I was 6. We knew we were going to do this since forever,” Klay says.

“Dad always wanted to put this place together to give us a chance to do this together,” Kalen explains.

“We have always been a tight family,” Klay adds. “Dad was always a together man. He always said, ‘If we don’t do this together, no use doing this at all.’”

Kyle’s plan is working. Today, the brothers raise a 400-head cow/calf herd and farm 2,500 acres of corn, sunflowers, wheat and millet together on the ranch where they grew up. Their sister, Kelsie, and her husband, Luke Meeks, ranch with Luke’s family near Interior.

“This is what he always wanted, and they do a really good job,” Kim says. “We were just holding things together; they have brought all the knowledge of their generation into the ranch. They do a much better job than we ever did.”

Klay explained that his dad encouraged them to leave the ranch, get an education and then put their ideas to work on the ranch. “The thing about dad, even when we were younger, he was the boss, but he never talked down to us like we were his employees.”

Talking about Kyle, his calm presence, fun-loving spirit and the way he mentored his children – always treating them as equals and individuals with valid input – is difficult. Kyle, 61, passed away from post- COVID complications just after Christmas, Jan. 7.

“Everything I do brings memories of him,” Kelsie says. “I have peace in knowing where he is.”

Klay adds, “I miss hearing his opinions.”

“You try to figure out what he would say. You know what he would say, but I want to hear it,” Kalen says.

Kim and Kyle were married 40 years. Kim says her children and eight grandchildren give her comfort. They are what keep her going and moving forward. “My kids and family are everything to me, absolutely everything.”

Cattle are an insurance policy for crops during drought

The ranch has been in Kim’s family for four generations, since her grandpa, Harry, homesteaded the land. When high school sweethearts, Kim Henschel and Kyle Harris married, they decided to continue the tradition. They began by working for Kim’s dad, Edward Henschel, and eventually bought the ranch from him in 2006.

Like their children, Kim and Kyle’s grandchildren enjoy the outdoors and the freedom growing up on a ranch offers.

“Living out here is really the best way to teach responsibility,” explains Heather, Kalen’s wife.

Her sister-in-law, Kasi, agrees. “It is just open and there’s freedom to run and play. I grew up in New Mexico, where you have neighbors and a fenced in yard.”

When Kalen and Klay returned to the ranch after college, they began increasing the cow numbers from around 150 to 400 head. They also began implementing no-till field management.

“We were tired of watching our fields blow away,” Klay says.

“And we don’t like tilling the ground because you lose moisture. Our fields that have been no-tilled the longest, that is where we see the biggest yield boost,” Kalen says. “We used to raise 30-bushel wheat. Now, with no-tilling, on a good year we can hit 60- to 70-bushel wheat.”

Retaining moisture is key – especially this year. Like many South Dakota ranches, the Harris ranch hasn’t received much rain this summer. “As soon as the corn got planted, it quit raining. We got a rain May 14 and early August, but that has been it,” Kalen says.

Due to the drought, they were unable to harvest their spring wheat, so they hayed it to feed their cattle instead. The brothers say because of dry conditions, they will probably end up chopping and feeding at least some of their corn acres as well. “Cattle are an insurance policy for crops. If you don’t get anything out of them, you can find a way to feed or graze them,” Kalen says.

The drought also impacts the way they manage their cattle herd. This summer they decided to wean and background their calves earlier. “It makes your pasture go farther and brings the cows into winter in better condition,” Klay says.

2020 was the first season the brothers had backgrounded calves. They said it worked out well for them, and they were able to market their cattle at a premium. And because their herd is known for maternal traits and stayability, they bangs vaccinate all the heifers they market so buyers have more options.

“When we were young, we flew by the seat of our pants. We would turn cattle out on the reservation in the spring and gather them in the fall. Now we pay more attention to them,” Klay says, explaining that like every other aspect of their operation, the brothers put a lot more planning and management into their cattle herd and utilize rotational grazing to maximize grazing acres.