Johnson Family

The Johnson family is deeply rooted in Hand County and South Dakota’s agriculture tradition.

Six of Curtis Johnson’s great-grandparents homesteaded in Hand County. Both his great-great-grandpa Thomas Cawood and great-grandpa William Walter Johnson served in the South Dakota Legislature in 1885 and 1889. The home he and his wife, Kelly, live in with their children, was built atop the same land as his great-grandpa Johnson’s sod house. And each growing season, Curtis Johnson plants and harvests in the same fields that his dad, Terry, Grandpa Walter, Great-Grandpa Thomas and Great-Great Grandpa William Walter planted and harvested.

“Farming land that has been farmed by four generations before me, makes me feel like I am the next in line to care for the land. It’s not quite like going out and buying something,” Curtis explained.

Curtis and Kelly returned to the family farm 20 miles south of Miller in 2015. The couple had been working in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho: Curtis as a mechanical engineer and Kelly as an occupational therapist. Together the couple owned an occupational therapy clinic.

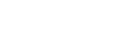

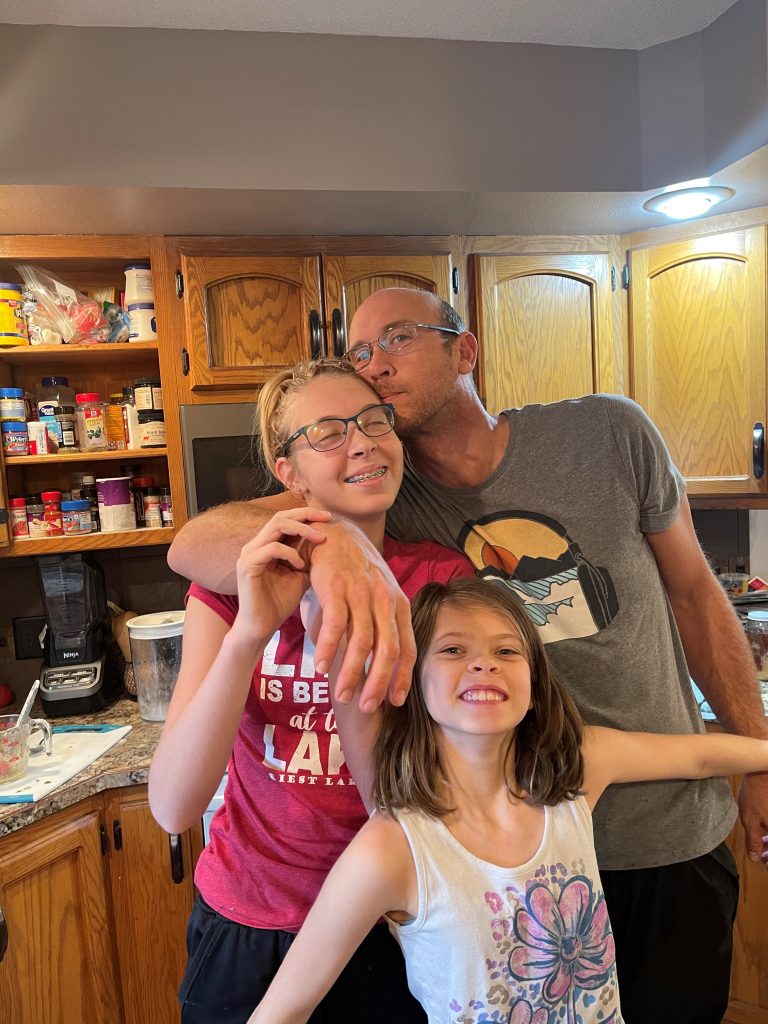

“We wanted to raise our kids on the farm,” Curtis said of their four children: Alexis, Brooks, Ava and Nikki.

Kelly, who grew up on a small Washington horse farm, agreed. “There is a big sense of freedom out here. Our kids can run around and do what they want to do. If they want to go ride their ATV, they can ride it. Or if they want to go shoot, they can.”

“And I can teach my kids skills out here,” Curtis added. “Like how to drive a stick shift and they have the opportunity to figure out how to fix things when they break.”

A mechanical engineering graduate of South Dakota School of Mines and Technology, Curtis explained how the hands-on experiences from his childhood on the farm came in handy.

“The engineering side of things was very second-hand to me. The math was very hard. It made me a unique engineer in a way,” Curtis said.

In addition to the farming lifestyle, Kelly appreciates the fact that her children are attending school and growing up in the rural community of Miller. “There is a sense of accountability in this small town. We know almost everyone who lives here. They know us and our kids. If the kids do something they should not be, I appreciate the fact that someone will step in and let me know or my kids know.”

To Kelly’s point, Curtis shared a story of when he was 18 years old. A farmer loaned him a pickup and trailer to haul some cattle home from a sale.

“When I dropped off the trailer, his wife said, ‘Wow, he let you drive his pickup. He does not even let me drive his pickup.’ And the farmer said to me, ‘I knew your grandpa. If I cannot trust you, I cannot trust anyone.’”

After the couple returned to the farm with their children, Kelly began working as an occupational therapist for Avera in Miller and Curtis began farming alongside his dad, Terry. Together they raise alfalfa, wheat, corn, soybeans and cattle. In addition to Curtis, Terry and his wife, Linda, raised daughters, Robin Musch and Jennifer Haring, on the family farm.

Terry says he was happy when he learned Curtis wanted to return home to continue the family farming legacy.

“I was tickled to death when I learned he wanted to return home to farm. I had kind of run out of steam so to speak,” Terry shared. “It is neat in the overall scheme of things, we have our name written in the dirt here.”

Since returning home, Curtis has slowly expanded the herd and pastureland. Most of the acres he purchases from neighbors at one time belonged to a great-grandpa, uncle or distant cousin.

Terry said he had a similar experience when he bought some quarters of land shortly after returning to the family farm as a Vietnam veteran.

“In June of 1976 I bought four quarters that had belonged to dad’s brother, Royal. We paid entirely way too much for the four quarters – especially looking at the year,” Terry said.

He shared that reclaiming this land for his family farm meant a lot to him. Unlike so many of the farm families who homesteaded in South Dakota in the late 1880s, his family was able to hang on to some of their farm ground through the Dirty Thirties. But it wasn’t easy.

“My dad, Walter, was a very young man. And his dad, William Walter Johnson, had died fairly young. So, Dad and Grandma Minnie had to work to keep the farm together, but they lost some quarters of land because they couldn’t pay the taxes.”

Terry and Curtis take extra steps when caring for the land that has been in their family for more than a century. Since the early 1990s, they have implemented no-till farming practices. And, when he can, Curtis implements rotationally grazing. Although he says the drought in the summer 2021 made it tough to implement the practice.

“I had to choose to either sell calves or over graze. I did not sell cattle. Thankfully it started to rain and now the grasses are really coming back,” Curtis said.

In addition to expanding grazing acres and cattle numbers, Curtis has worked to update the farm’s equipment and technology. “By adding autosteer, I am able to get 12 more rows into one quarter.”

He has also changed the way he markets commodities.

“I am working to get a better analysis on breakeven numbers, and I hired a marketing firm to help me,” Curtis explained. “This has given me the ability to market grain before harvest to cover breakevens.”

On average, Curtis markets about 60 to 70 percent of his crop prior to harvest. “It gives me the confidence when planting that I will turn a profit,” said Curtis, explaining that the farm’s risk management strategy includes a bailout plan if weather extremes don’t allow him to harvest the pre-marketed bushels.

“Before I started marketing this way, there was so much stress associated with the markets. I still watch the markets, but it is not as critical when 60 percent of the corn is sold before harvest,” Curtis said.

Curtis added that he relies on the marketing firm he works with for guidance. He looks to them as a coach of sorts as he and Kelly navigate the ins and outs of farming his family’s land for the next generation.

“Who knows, maybe one day, one of our kids will want to take over the farm for the next generation,” Kelly said.