Konechne Farm Family

Throughout hunting season, biscuits and gravy, eggs, bacon, French toast and of course hot coffee, greet hunters each morning at the Konechne Red Barn Lodge. Kayla Konechne gets up to her alarm at 5:30 a.m. to make sure everything is hot and ready to enjoy.

“We’re a family-style lodge, so we try to keep things laid back – including our meals. Everything is prepared fresh each day, but I serve buffet style because I figure, they are grown men, they don’t need me to monitor their servings,” says Kayla, who in the off season works as a Registered Nurse for clinics in Kimball and Chamberlain.

“I was tired of a time clock and was ready to be in control of where my life was heading instead of helping someone else get where they needed to be.”

kelly konechne

Kayla manages the hunting lodge with her husband, Kelly. The couple took on this opportunity seven years ago, not long after they returned to Kelly’s family farm near Kimball. The hunting lodge is owned by Kelly’s dad, James and brother, Chris.

“I was tired of a time clock and was ready to be in control of where my life was heading instead of helping someone else get where they needed to be,” Kelly says. He explains that for their family’s farm, there are many ways the hunting lodge works well as a side business because it compliments the family’s cow/calf, backgrounding, custom feeding and finishing operation.

For starters, their farm is already a family-run business. “We do things a bit different from some lodges. We provide family-style hunts,” Kelly says of the hunts that operate around a loose schedule set by the hunters. “We’re not the place where you have to be on the bus by a strict time every morning.”

And when it comes to providing habitat for the pheasants, the family has been implementing conservation practices, like no-till farming, long before it was commonplace, explains Kelly’s dad, James.

“I was one of the first people in this area and I kind of got laughed at. It was a tough start. That first year, I was nervous to try something new, so the first field I tried it in was not along a road – thank goodness,” says the 67-year-old farmer of the first no-till field in 1993. “In 1994, though we had tremendous luck and yielded 170 bushels of corn, which was very unheard of.”

That field was roadside and neighbors began asking questions.

In addition to no-till, the family began adding cover crops to their diverse cropping rotation. “Cover crops are a tremendous asset,” James says. “Not only are they good for the ground, they are tremendous for livestock feed. Cattle love turnips and radishes. When we turn them out in the fall, they go after them like candy.”

Most crops raised on the Konechne farm end up as livestock feed. In addition to dryland corn, the family also raises rye, alfalfa, oats and forage sorghum. “In the area where we live, there is a lot of rough ground,” James explains. “Not exactly good farm ground. So, cattle are a good avenue for marketing our crops. We plant a lot of odds and ends that end up as silage.”

The cattle also get to graze down the pheasant foodplots each spring. A practice which Kelly says gets them in good shape for calving. “The cows are out there moving around and the calves present themselves as they are supposed to instead of backwards. Since we started grazing foodplots, we have not seen near the calving or health issues as we did in the past.”

The foodplots are replanted to a corn and sorghum blend after calving season, around mid-June, so they are ready to go by the time pheasants need winter cover. Kelly says there is enough land on the farm that he can guide three-day hunts and take hunters to a new location each day.

Some of the land they hunt and raise cattle and crops on is the same land, James’ dad, James Sr., purchased in 1948 after returning from serving in the Army Air Corps during World War II. “He got started with $100 cash and borrowed horses,” James explains.

His dad was able to save up the $100 he used to purchase the farm, hand-picking corn in Minnesota for 3-cents-a-bushel. In 1976 after he graduated from South Dakota State University with an Agriculture degree, James got his start farming with his dad, and his brother, David.

David started the hunting lodge in the mid-1980s. Nearly a decade later, he relocated an old barn from 3 miles away and converting it into the lodge. When he was ready to retire, James was not in the position to purchase the business so David sold it along with some of the original land purchased by James Sr. to an out-of-state interest. With Kelly and Kayla now on the farm and willing to manage the business, James saw this as a good time to regain the family land.

“My dad worked hard to get it all put together, I hated to see it go off to a total stranger like it did. This allows us to keep it in the family so to speak,” James explains.

Keeping the farm in the family has been a focus of James for many years. When he and Audrey’s oldest son, Chris, decided to return home to farm after receiving an Agriculture degree from Mitchell Technical Institute, the men began looking for ways to expand what was at that time, a small feedlot operation.

“We started buying a few more small calves, fixing up an old yard, fixing up another old yard, building some new fence. We expanded slowly. It was like taking an old house and adding on and adding on and before you know it, we had room for 2,000-head,” Chris says.

Since he first returned home, making it in the cattle business has become a lot more complicated. “When I think back to when I first started, it was easy. As our operation has grown, the industry has also changed,” Chris says. “There are too few people to sell the cattle to. The markets are controlled by too few active buyers.”

To remain competitive, he, his dad and brother, Kelly, have had to modify their herd genetics. Today, they raise smaller cows. “My goal is to sell potloads of cattle that are most attractive to buyers weighing about 700-900 pounds.”“Some grandparents talk about only getting to see their grandkids once every six months or once a year. It seems like there is always a grandkid playing here.”

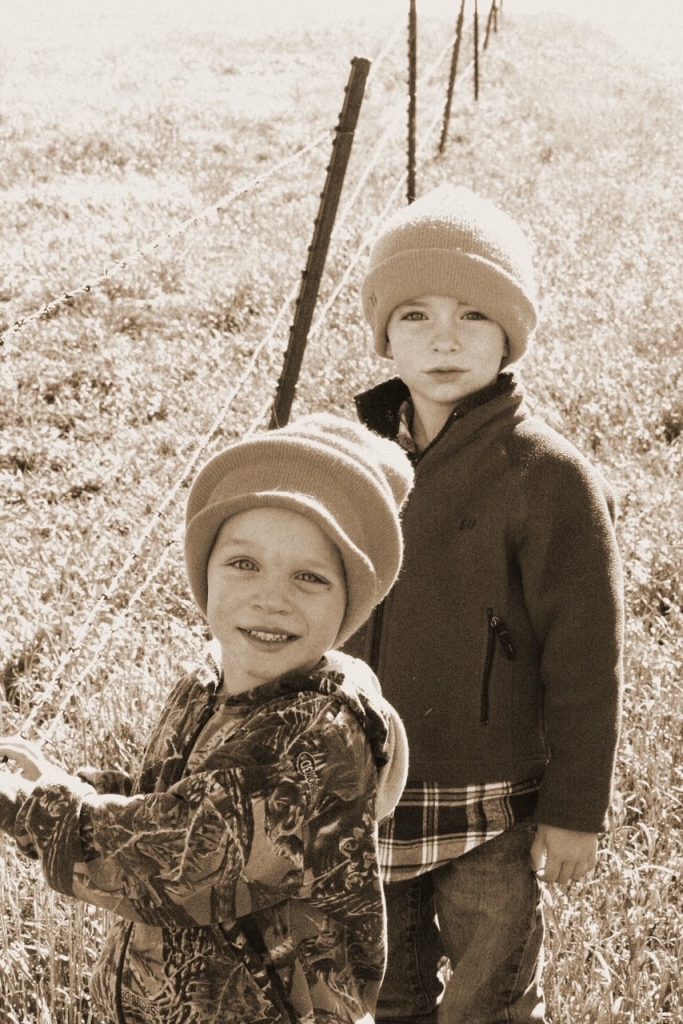

Even though it’s challenging, Chris says farming is all he ever saw himself doing. And now that his kids have started helping out, he says he thinks about what he is doing today as a way to preserve the family’s farming legacy for the next generation. “Last spring when the kids were remote schooling, our 8-year-old son, Leo was more ambitious than me to want to get up and go out to work.”

The work ethic is also one of the reasons, Chris’ wife, Amanda is happy to raise their children on the farm. “The work ethic and hands-on skills I feel are important for our kids to learn. And regardless of where they end up one day, I feel like these are worthwhile skills to have,” says Amanda, who owns her own graphic design business.

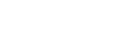

Amanda and Chris’ children are Leo, 8; Violet, 6; George, 5; and Jasper, 2. The family only lives a quarter mile from Kayla and Kelly’s children, Cadence, 12; Carter, 10; Olivia, 7 and Ty, 6. And a quarter mile from Grandma Audrey.

Audrey says she is happy she was able to raise her six children on the farm and enjoys being able to be actively involved in at least some of her grandkids’ lives. “Some grandparents talk about only getting to see their grandkids once every six months or once a year. It seems like there is always a grandkid playing here. I have never had an empty nest. Our oldest was home to farm with us before the last one was in school.”

Audrey enjoys her grandma duties and sharing her time, energy, and strong Catholic faith with the next generation. “We both grew up attending church and I went to a catholic school, in Rapid City, so when we got married, we never thought of doing anything different when we raised our own children,” she says.

In addition to Chris and Kelly, James and Audrey’s son, Kevin also lives on the farm with his wife, Heather.

Like his dad and brothers, Kevin is self-employed, operating Diamond K Trucking.

“I was looking for an opportunity to be self-employed. I went to school for welding, and after four years in a factory, I got kinda bored with it,” says Kevin, who took inspiration from his Grandpa James’ brand for his business name and logo. “Grandpa started Box K Ranch. I wanted to be different, so I turned the box a bit and made a diamond.”

Kevin says he and Heather, chose to live on the family farm because they think it is a good place to raise children. They are expecting their first child in January.

“I was raised on a farm by Watertown and I absolutely loved it. Because we lived in the country, we played less sports in school. But I learned a lot about hard work with my family,” says Heather, who is the Disbursement and Donations Supervisor at St. Joseph Indian School “I played in the dirt and mud. When they took us fencing, we got to play in the river. And I spent a lot of time with my grandparents, because dad farmed with Grandpa and they only lived a mile away – just like it is for us here.”

Even though each of her daughter’s-in-law have full days with children and work, Audrey says they all spend quite a bit of time helping their spouses wherever they’re needed on the farm.

“When it’s harvest, they are driving machinery with a pillow and at least one sleeping child – or they are helping to work cattle. You know, you don’t hear about farmer’s wives that often, but like our son’s wives, most of them have a job and they help their husband on the farm, and they take care of the kids,” Audrey says.

The three Konechne children who live off the farm with their families are: Grant and his wife, Jolene who live in Huron with their three children, Holly, Charlie and Rory. Laura and her husband, Bret Sitzmann live in St. Louise, Mo., with their children, Dylan and Hannah. And Taylor, and his wife, Nataly who live in Los Alamos, Calif.

James says he is happy his sons continue the farming tradition. “The operation sure would not be going if I didn’t have the two boys here. I would have had to quit by now,” he says, explaining that in his early 40s he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Although his symptoms have stabilized, his mobility is greatly reduced. “It’s a terrible feeling when you have to change your lifestyle, and farming has been your lifestyle your entire life. Most of us never want to quit or slow down or step back and watch other guys do the work.”

However, thanks to a side-by-side and a lift they added to the combine this harvest, James continues to be involved in daily farm activities. He explains that it’s the farmer in him that figures out ways to stay involved. “Farmers have to make do with what we got so to speak. We often have to figure out ways to make things work. You can’t just run to town and buy yourself out of a situation.”