Stroschein Family

By Lura Roti for SDFU

Sometimes history repeats itself. And Brown County cattle producer Larry Stroschein is happy it did.

“My Grandpa August was born and raised in St. Paul, Minn. And when he was a young man, in his mid-teens, he and his buddy jumped on the Milwaukee Railroad and came out here to help with the harvest. While he was here, he met Ida Brick and they eventually got married and the city boy became a farmer,” Larry shares.

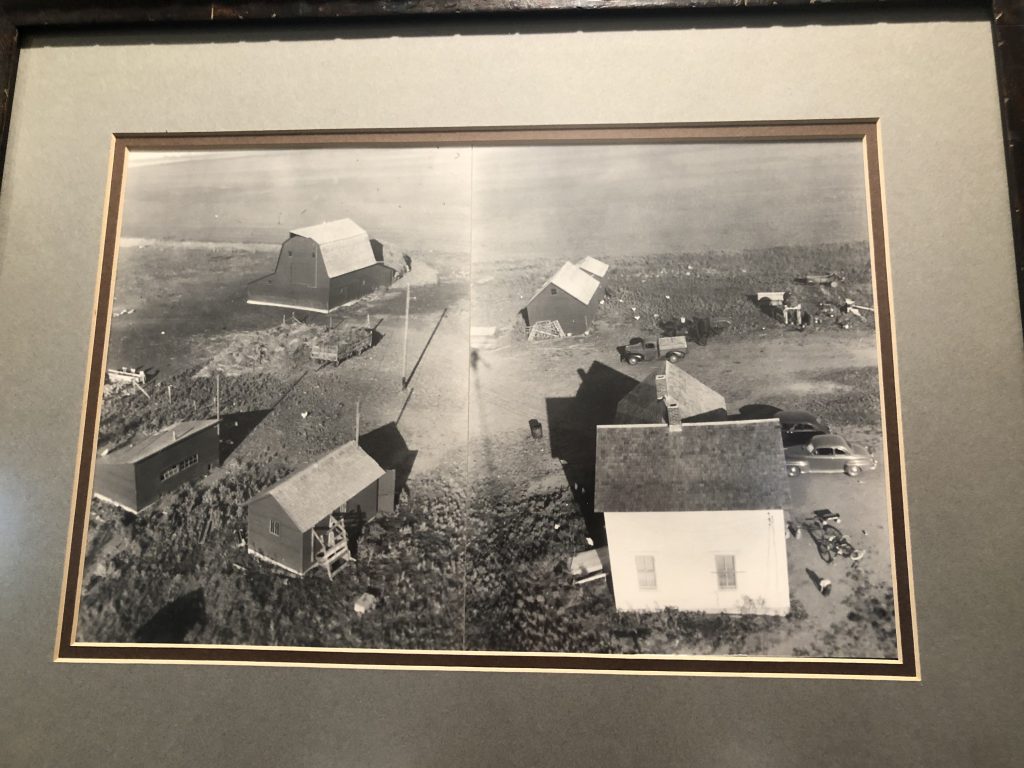

Nearly a century later, Larry and Sharon’s daughter, Amy, married John Wanous and today, the couple manages the family farm – rotational grazing cattle on some of the same land August bought 10 miles west and one mile south of Warner in 1912.

“Let’s face it, most of the time it’s a son that’s taking over the farm, not a daughter,” Amy says. “We love living out here. I just cannot imagine living anywhere else in the world. If anyone said I could go anywhere, I would not move.”

Her husband, John, agrees. Although John had much more experience than Larry’s Grandpa August, like August, he grew up in town. His dad and namesake, John Sr., served as general manager of the local Warner Co-op. “I have been an animal nut since I was a kid. I always worked for farmers growing up,” John explains. “There is no way a young guy could get started in agriculture today without any ground. Without Larry and Sharon, this would not be possible.”

The fact that four generations later, the family continues to raise cattle on the original land August purchased more than a century ago is amazing. Because like so many of South Dakota’s farmers and ranchers, during the Dirty Thirties, August wasn’t able to make his payments and lost the farm. “Back in those days, banks would not work with you,” Larry explains.

“Grandpa didn’t talk about it much, but one Sunday after dinner I heard Dad and Grandpa talking about how it all happened. In 1928, Grandpa had a tremendous wheat crop. There were three farm magazines he had a subscription to, and they all told farmers to “hold your wheat, it will go to $3 a bushel.” It was pie in the sky. He held his wheat and got 28 cents a bushel and could not make his payment. If he had sold it in ’28, he would have gotten $2.75 a bushel and been fine.

In 1945 the land came up for sale and Larry’s dad, Lester, who had been farming leased ground, bought the family’s farm and rangeland back from the insurance company who foreclosed on his dad, August.

“My dad did get $3 a bushel for the second wheat crop he took off the homeplace in 1947. He went straight to Ernie Rhodes’ office in Aberdeen and said, ‘I came in here to pay off the farm.’ Ernie said, ‘you mean you are here to make your yearly payment.’ Dad said, ‘no, I am here to pay it off.’ Then Ernie said, ‘I knew I sold that farm too cheap.’”

With a legacy like this, Larry is thrilled that when he was ready to retire, Amy and John wanted to take over the day-to-day farm operations.

“It makes me feel really good. And maybe one day, one of the grandkids will want to take it over,” Larry says.

Growing up helping his dad, Lester, on the farm, Larry says he always knew he wanted to continue the family tradition of raising crops and cattle. Even though the family raises some forage crops, it’s really the cattle that they are passionate about, Larry explains.

“You get a bull you like and match them up with your cows and you take the heifers from the bull you picked out with your cows and you keep the best heifers and match them and pretty soon the herd becomes a part of you because you basically made the herd the way it is.”

Even today, as a retired cattleman, Larry says he loves nothing better than spending time with his cattle.

“Most farmers, when they retire, they buy a boat and they go out in the middle of a lake with a cooler of beer and fish. I will take my beer cooler and go sit in the middle of a pasture and just watch my cows. And pretty soon the little calves will come nuzzle my fingers. Then, when I’m done, I head home and I don’t have any fish to clean.”

Oddly enough, it was a runt piglet that helped Larry get his start in the cattle business.

“My mother’s family were farmers too, and they raised hogs. They had a real runt pig and Grandpa said I could have that runt pig if I could catch it. Well, I couldn’t catch it, so I drafted my Uncle Merlyn and he helped me. Well, we all milked cows, and that dumb runt pig got all the separated milk and grew up to be one big pig. I traded it to my dad for a little heifer calf and I started keeping her heifers.”

Because they run all the cattle together, to keep Larry’s cattle separate from Amy and John’s, Larry’s cattle are red and the Wanouses’ cattle are black.

Not unlike his Grandpa August, Larry and Sharon faced tough times in the 1980s. It was during the Farm Crisis of the ’80s that Sharon returned to off-farm work. Prior to children, Sharon taught elementary school, first in Mellette then in Warner after she and Larry married in 1965.

Sharon and Larry have four grown children and 10 grandchildren: Amy and John and children, Andrew, Elizabeth, and Katy; Ryan and his wife, Angela, and son, Will; Lon and his wife, Mindi, and children, Grace, Dawson and Oliver; and Allyson and her husband, Pete, and children, Sophie, Alexander and Freya.

After their children were in school, the banker encouraged Sharon to get an off-farm job. So she began working as the Northeast Area Director for Sen. Tim Johnson. She held that position for 28 years, retiring in January 2015.

“That off-farm income and health insurance was vital to our operation,” explains Sharon, who grew up on a farm 17 miles northwest of Aberdeen. Today, like the Stroschein farm, the Raetzman family farm remains in the family.

“Growing up on the farm, I thought this was the life. There was the freedom and animals and I had my own horse,” Sharon says.

Today, it’s their grandchildren who enjoy riding and competing in 4-H horsemanship. And like her mom, Amy supplements the family’s farm income by working for the Warner School District.

With Amy working full time during the school year, to keep the workload more manageable for John, the family calves twice a year – in April and August.

“It also gives you two different markets to sell into and you get two shots with your bulls,” Larry explains. “I feel I can spend more money for a bull because he will breed double the number of cows.”

Much of the land their cattle graze is still native grassland.

“We can still see the wagon wheel trails from the pioneers and old settlers,” Larry says.

To best manage their grassland, the family implements a strict rotational grazing plan. “I like the concept of rotational grazing because it’s going back to when this land was all prairie and the buffalo roamed. The buffalo would eat different grasses different times of year. You can do that with rotational grazing,” Larry says.

He explains that he, John and Amy force the cows to graze a pasture hard for about three weeks, and then they take the cows out. “It is amazing how that grass will recover,” Larry says.

Each year, the family’s herd rotates through different pastures different times of year, giving both warm- and cool-season grasses an opportunity to thrive. They have seen a resurgence of big bluestem.

“Much of this land has never had a plow go through it and if it’s up to us, it will never have a plow go through it,” says Amy. “We think of ourselves more as ranchers anyway. It’s the cattle we are passionate about.”